The safety-focused content at CJP 2023 concluded with back-to-back presentations by Master CFI Neil Singer addressing critical aspects of safe aircraft operations.

(No) Slip-Sliding Away – Landing Performance and TPL

Singer began with an extensive look into landing performance data and computing the touchdown point limit (TPL) at which a pilot should perform a go-around if the wheels aren’t yet planted firmly on the runway.

“The FAA says that when our Part 23 Airplanes are certified, the procedures used for determining the [landing] distance must be consistently executable by pilots of average skill,” Singer explained. “However, they also say the actual output [from company test pilots] is not realistic, so the procedures can be super wonky.”

Operators under Part 91 are legally permitted to land on a runway within the length described in the AFM, which pilots might incorrectly interpret to mean their aircraft is safe to land on that runway. “There is a FAR that says that if we have a certified AFM, we must comply with the restrictions in Chapter Two, Section Two of the AFM’s commutation section,” Singer noted. “In your Section Two, there’s a limitation that tells you how you have to comply with takeoff and landing limits.

“And so, a little bit of a long road to get there, but you do actually have a legal requirement for Part 91 to follow that,” he added.

Singer then explained how some “small excursions” could potentially result in an overrun on a 4,000′ runway for an aircraft approved to land in 3,000 feet. “Every knot above VREF adds 40 feet to your landing,” he noted. “In this particular case, this pilot is going to see 200 feet [added to] the AFM landing distance required.

“What if he’s also 20 feet too high? Seventy feet over the 50-foot threshold?” he continued. “Do the math and work out that every extra 10 feet high is going to add about 200 feet to your landing distance. What if you take an extra second to lower the nose? At 100 knots groundspeed, you’re covering 170 feet per second.”

What initially looked like a comfortable 1,000 foot safety margin can quickly become harrowing if pilots are “a little fast, a little high and floating,” Singer concluded. Thus, the importance of a runway safety margin and computing a TPL that, if exceeded, prompts the pilot to go around for another attempt.

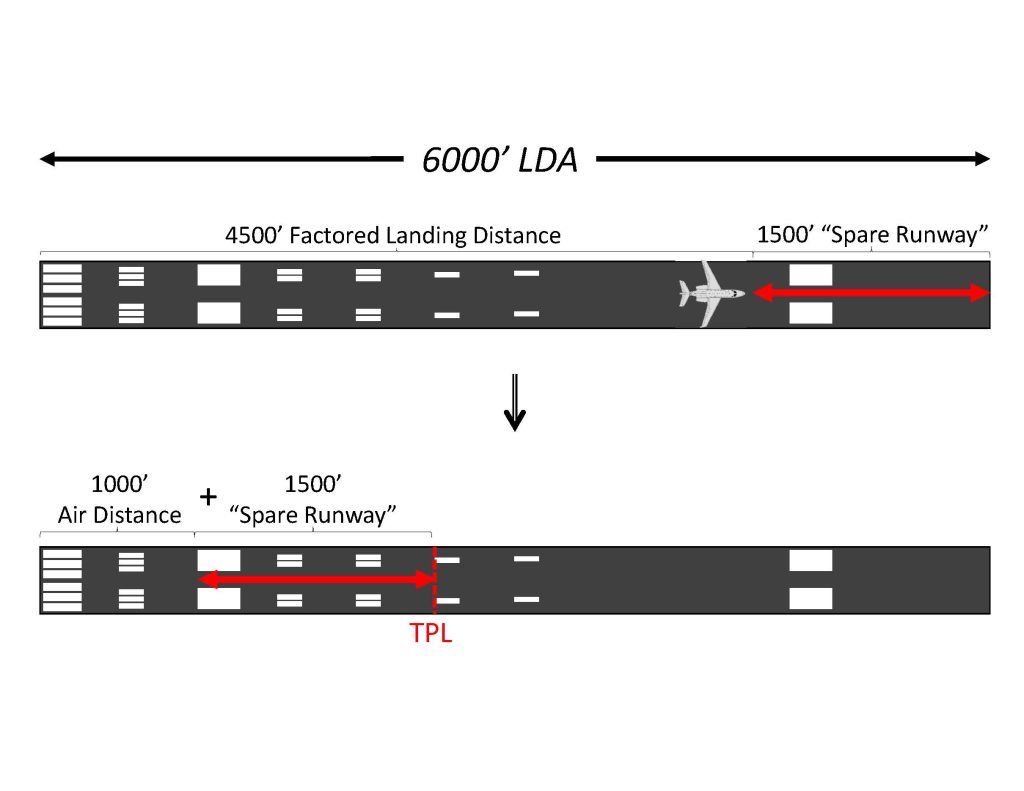

“Imagine we’ve computed our performance to land on a 6,000′ runway and, with our safety factor, we need 4,500 feet to land,” he said. “That’s 1,500 feet of spare runway, right? Well, imagine we’re going to need 1,000 feet of air distance for landing. We’re then going to take that spare runway, back it up and add it to that air distance to the spare runway. That’s our TPL.”

A Crossing Gone (Very) Wrong, Redux

In his second presentation, Singer revisited a case study he presented back in 2016 at the CJP Convention in New Orleans: the October 2009 forced landing of a Piaggio P.180 Avanti turboprop twin in Greenland following a series of poor decisions made by the pilot ferrying the aircraft from Kuwait to Dallas, TX.

The accident occurred during a leg from Keflavik, Iceland (BIKF) to a fuel stop in Narsarsuaq, Greenland (BGBW). As the aircraft wasn’t approved to operate in RVSM airspace, the pilot filed at FL270 for the planned 750-mile flight – the first ‘hole’ in what would ultimately prove to be a textbook case of the Swiss cheese model of accident causation.

According to the subsequent Danish Accident Investigation Board (AIB) report, just 40 minutes of fuel reserve would have remained if flying at long-range cruise power settings; had he been able to climb to FL280, flying with maximum continuous power – the setting the pilot used on the flight – would’ve left just 11 minutes of reserve.

The pilot departed and, encouragingly, was initially cleared to FL270. “However, before he hits the boundary of Iceland’s domestic airspace and reaches the Reykjavik Oceanic Area, he’s instructed to descend to FL200,” Singer said – adding significantly to the fuel burn.

Still, the pilot was able to reach Narsarsuaq, but “this is where things really start to fall apart quickly,” Singer continued. “The conditions absolutely should have allowed for him to successfully get in … but he starts the approach hot and passes within four nautical miles of the NDB at 9,000′ when he could have been as low as 1,500′.”

Add in a cloud layer at 3,000′ AGL and the pilot opts to go missed on the approach. “The pilot tells controllers that he can’t get into Narsarsuaq, and the guy sitting on the ground [at the airport] replies that ceilings are at 3,000 feet. But the pilot completely disregards this information and says he’s going to divert to [Kangerlussuaq Airport at] Sondrestrom.”

ATC suggested a closer alternate of Nuuk (BGGH) that offered a 3,100′ runway more than 100 nm closer to the pilot’s position than Sondrestrom. However, the operator had chosen an FMS airport database that only displayed airports with runways of 4,000′ or greater. The pilot rejected the suggestion and continued toward Sondrestrom.

That said, “the Danish AIB recreated that had he gone to FL 280, he would have needed 721 pounds of fuel; when he went missed, he had 780 pounds,” Singer said. “This is right down to zero margin, but it was still salvageable. We haven’t lost the flight yet.” However, ATC limited the pilot to FL190 due to a flight of two F-16 fighter jets scheduled over southern Greenland, out of radar and radio contact.

“We’ve whittled the margins down so much now that we’re essentially at zero,” Singer lamented.

It’s at this point when the pilot finally takes PIC authority and, without a clearance, climbs to FL320. “It’s the first time that he really made a good decision this entire flight,” Singer said. “The FMS shows 60 pounds of fuel; he could stay up nice and high, get right outside Sondrestrom airport and then – please don’t screw up this approach – get the plane on the ground. Maybe.

“But instead, he really puts the final nail in the coffin and shuts down an engine to conserve fuel,” he continued. “I mean, I can sort of respect the intuition behind this. ‘I’m burning twice as much gas with two engines!’ Unfortunately, it actually decreases the per mile efficiency by 10 percent.”

Upon this realization, the pilot asks for vectors out to the ocean for a ditching, but “at this point he’s closer to Sondrestrom than he is to the ocean,” Singer said. “He’s clearly really lost situational awareness and he’s getting into panic mode. At this point, the Swiss cheese is lined out.”

The flight ended on an ice cap 70 miles from Sondrestrom with “the left engine shut down and the right engine still running with a teaspoon or so of fuel in it,” Singer noted. Despite the fuselage breaking into several pieces, the pilot amazingly survived the accident with relatively few injuries – but, he still managed to make one final error.

“This one makes me cringe,” Singer said. “He turned his transponder off to save power. I don’t even know what that means. He had an engine running, so he had a generator!” Fortunately, a rescue helicopter had already been dispatched and the pilot was rescued, even with reported cloud ceilings at his location just 500 feet above the surrounding terrain.

“This guy was so lucky,” Singer concluded. “Unbelievably lucky.”